While I haven’t been vocal about it, work has continued, in off moments and stolen time, on the online edition of Claude McKay’s Harlem Shadows which I described some time ago. At the present moment, Roopika Risam and I have collected nearly all the textual variants and have marked them up in TEI; we added (as yet unproofread) versions of early reviews and other supplemental material (and still more is being hunted down and added); and there is enough XSLT and CSS to hold the whole thing together, more or less. It is very much still a work in progress, but you can see the current state of its progress here.

This process has also been an opportunity to understand the textual history of the poems of Harlem Shadows, including the relationship of the collection Harlem Shadows to McKay’s earlier collection Spring in New Hampshire. The Jamaican poet who travels to rural Kansas in order to pursue a degree in agriculture and ends up being one of the early voices of Harlem Renaissance, manages to do so by passing through not only Harlem, but New Hampshire and, crucially, London. Spring in New Hampshire was how many readers first encountered McKay (including readers like Charlie Chaplin and Hubert Harrison), and the collection offers a valuable first draft of Harlem Shadows.

The collection Spring in New Hampshire was first published in 1920. Its “Acknowledgments” page notes two facts which underscore this volume’s importance in the emergence of Harlem Shadows.

First, when Spring in New Hampshire appeared, an American edition of was clearly imagined as immiment. But the American edition, purportedly “being published simultaneously by Alfred A. Knopf,” never materialized. What did appear, two years later (published by Harcourt, Brace, and Co) was Harlem Shadows.

And if Harlem Shadows is substantially indebted to Spring in New Hampshire About one third of Harlem Shadows’s poems appear in Spring, among them “Tropics in New York,” “The Barrier,” “North and South,” “Harlem Shadows,” “The Harlem Dancer,” and “The Lynching”., Spring in New Hampshire in turn is less an origin than another gathering point for poems culled from elsewhere; this is especially the case of a large selection of poems which appear in the Summer 1920 issue of The Cambridge Magazine. This latter includes 23 of Spring in New Hampshire’s 31 poems. And, with the exception of the dedication of “Spring in New Hampshire” (dedicated in Spring to “J. L. J. F. E.”This would almost certainly be Dutch bibliophile, and the man in part responsible for McKay’s trip to London, J. L. J. F. Ezerman (Gosciak 117).), there are no textual differences between the poems as they appear in CM and as they appear in Spring.

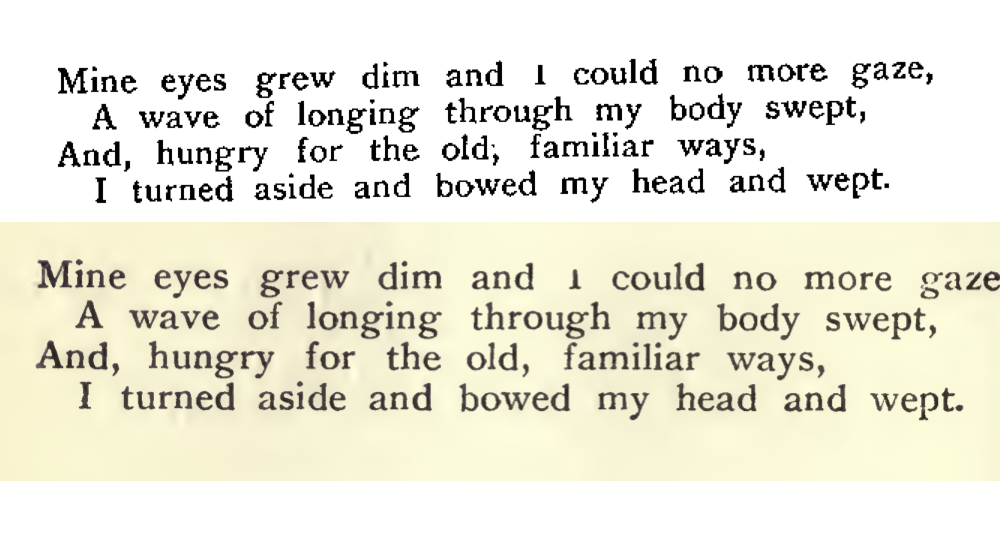

To secure the point I’m moving towards, compare these images, taken from the appearance of “The Tropics in New York” in Cambridge Magazine (top) and Spring in New Hampshire (bottom): My thanks to Nicholas Morris who takes no responsibility for this conjecture, but was enormously helpful in discussing its plausibility.

Do you see that imperfection in the ‘I’ of “I could no more gaze” in both versions. Does they look identical to you too? It seems reasonable to conjecture that the Cambridge Magazine poems and Spring in New Hampshire were both printed, if not from a single setting of type, then at least from a setting of type which likely included some of the same typeset material (in either monotype, linotype, or set by hand) from the Cambridge Magazine.In the interest of full disclosure, there is a similar imperfection in the Cambridge Magazine text of “When Dawn Comes to the City” which does not appear in the Spring in New Hampshire; but this does not vitiate the possibility, and evidence, suggesting the two texts represent something like a single setting of type.

The circumstances surrounding Cambridge Magazine likewise seem to confirm this possibility. Cambridge Magazine, at the time, was run by C. K. Ogden, with whom McKay spent time while visiting England in 1920. Ogden ran the magazine in collaboration with a number of his friends (among them, I. A. Richards). Of Ogden, McKay would write in his autobiography A Long Way from Home: “besides steering me round the picture galleries and being otherwise kind, [Ogden] had published a set of my verses in his Cambridge Magazine. Later he got me a publisher” (71). If McKay means that Ogden secured the publisher for Spring in New Hampshire (and that seems the most likely meaning here), it would certainly make sense that Ogden would go through the same publishing channels (including, perhaps, the same printer) as for the periodical for which he was responsible. The frontmatter of Spring in New Hampshire (published by Grant Richards), lists the printer as “The Morland Press.” And while Ogden (according to Josh Gosciak) authored the prefatory note for the appearance of the poems in Cambridge Magazine, it was I. A. Richards (a friend of Ogden’s, who regularly appeared in the Cambridge Magazine, including the Summer 1920 issue in which McKay’s poems appeared) who wrote the note the Spring in New Hampshire (after, according to McKay, George Bernard Shaw declined to write such an introductory note, Long Way Home 55).

All of which is interesting and worthy of note insomuch as it suggests that Harlem Shadows, key document of the Harlem Renaissance, has its origins not only in Jamaica and New York, but in New Hampshire and London. This eclecticism was vital to Ogden’s interest in McKay; Ogden was at this moment, working with I. A. Richards on what would emerge as “Basic English.” In BASIC, “Ogden wanted a usable language that reflected the hybridity of the changing dynamic of cultures and languages in the Caribbean, Africa, the United States, and Asia” (Gosciak 102). And in McKay, Ogden believed he had found a uniquely valuable voice in the development of such a language—a language, Gosciak describes, which would “decolonize the dominant ideology that espoused war and imperialism” (103).

Yet, the way in which McKay and Ogden imagined this decolonization of English is somewhat surprising. McKay came to Ogden frustrated with what he perceived to be the limitations of his previously published poetry, in Jamacian dialect. Here is Gosciak again:

[McKay’s] reputation was as the “Bobby Burns” of Jamaican folk wisdom, who could write persuasive “love songs” in a sonorous dialect. But an exasperated McKay explained to Ogden: “One can’t express any deep thought to perfection in it, nor can it effectively bring forth the note of sorrow.” Dialect was hackneyed, McKay concluded. “I’ve buried it and don’t care to revive it again.” Ogden was sympathetic to the poet’s desires to internationalize his poetics, and he mentioned him in precision and exactness—de-emotionalizing his lyrics of the charged baggage of Harlem and race. (104)

This tension is manifest in a disagreement between Ogden and McKay over what to title the collection. Ogden was interested in developing an international English, Gosciak, drawing on material in the Papers of CK Ogden explains:

McKay was opposed to [the title] Spring in New Hampshire, and Other Poems; he believed the title conjured associations with New England, which he felt was “played out”… McKay preferred “a terse, simple thing” for a title, such as “Poems or Verse,” which Ogden, too, appreciated. But McKay also had an eye for the New York—and Harlem—reading public. He suggested “Dawn in New York,” invoking imagery that would ultimately give texture to Harlem Shadows in 1922. Ogden persisted in his claims for the high lyricism of Frost, and eventually McKay came around to that aesthetic ground. (The choice of title, Spring in New Hampshire, was, as McKay acknowledged, a bold move for a poet who would very soon reprsent the Harlem Renaissance.) (Gosciak 105)

There is sort of confusion of motivations here; McKay’s frustration with dialect and Ogden’s attempt to decolonize English both find expression of in the poems of Spring in New Hampshire—poems that rely on traditional forms—sonnets aplenty!—and frequently Victorian diction. Yet, Ogden’s vision of de-colonizing English also involves de-racinating, with the effect that Ogden preferred to see McKay’s verse avoid any allusion too direct to Harlem or race.

And so Spring in New Hampshire ends up being as notable for what it doesn’t share with Harlem Shadows as what it does. The most famous poem of Harlem Shadows, “If We Must Die,” had first appeared in The Liberator in 1919, but it was not included in Spring in New Hampshire. In A Long Way Home, McKay recounts bringing a copy of Spring in New Hampshire to Frank Harris, of Pearson’s Magazine (who had wanted to publish “If We Must Die,” though he lost out to The Liberator):

[Harris] was pleased that I had put over the publication of a book of poems in London. “It’s a hard, mean city for any kind of genius,” he said, “and that’s an achivement for you.” He looked through the little brown-covered book. Then he ran his finger down the table of contents, closely scrutinizing. I noticed his aggressive brow becoem heavier and scowling. Suddenly he roared: “Where is the poem?… That fighting poem, ‘If We Must Die.’ Why isn’t it printed here?”

I was ashamed. My face was scorched with fire. I stammered: “I was advised to keep it out.”

“You are a bloody traitor to your race, sir!” Frank Harris shouted. “A damned traitor to your own integrity. That’s what the English and civilization have done to your people. Emasculated them. Deprived them of their guts. Better you were a head-hunting, blood-drinking cannibal of the jungle than a civilized coward. You were bolder in America. The English make obscene sycophants of their subject peoples. I am Irish and I know. But we Irish have guts you cannot rip out of us. I am ashamed of you, sir. It’s a good thing you got out of Engliand. It is no place for a genius to live.”

Frank Harris’s words cut like a whip into my hide, and I was glad to get out of his uncomfortable presence. Yet I felt relieved after his castigation. The excision of the poem had been like a nerve cut out of me, leaving a wound which would not heal. And it hurt more every time I saw the damned book of verse. I resolved to plug hard for the publication of an American edition, which would include the omitted poem. (81-82)

McKay here ends up being caught between two white editors, and their respective ways of imagining a response to British colonialism. (This situation recalls that of McKay and his relationship to dialect poetry discussed in Michael North’s excellent chapter in The Dialect of Modernism.)

That American edition that McKay resolves to publish after this encounter with Harris would, of course, be Harlem Shadows. Harlem Shadows, in McKay’s depiction, is a version of Spring in New Hampshire and a repudiation of it. Elsewhere in his autobiography he writes, “I was full and overflowing with singing and I sang all moods, wild, sweet, and bitter. I was steadfastly pursuing one object: the publication of an American book of verse. I desired to see ‘If We Must Die,’ the sonnet I had omitted in the London volume, inside of a book” (116).

Yet, if McKay’s comments encourage us to read Harlem Shadows as a re-politicized version of Spring in New Hampshire, “If We Must Die” itself, nevertheless, famously operates by abstracting the political violence of the “Red Summer” of 1919 into an unspecified “we kinsmen” against a “common foe.” And, indeed, Harlem Shadows, like Spring in New Hampshire, does not include some of McKay’s most explicitly political poetry of this period—poems like “To the White Fiends” or “A Capitalist at Dinner,” which were initially published in the same period, and in the same venues, as poems like “If We Must Die,” remain excluded.

All of which indicates the value of a comprehensive collection of all the contemporary poems and material which went into the making of Harlem Shadows—both through their inclusion and their exclusion.

Appendix: Tables of Contents Compared

Below I’ve preserved the original orderings of the tables of contents for both Harlem Shadows and Spring in New Hampshire and used color (a lovely salmon) to indicate which titles are shared.

| Harlem Shadows | Spring in New Hampshire |

| The Easter Flower | Spring in New Hampshire |

| To One Coming North | The Spanish Needle |

| America | The Lynching |

| Alfonso, Dressing to Wait at Table | To O. E. A. |

| The Tropics in New York | Alfonso, Dressing to Wait at Table, Sings |

| Flame Heart | Flowers of Passion |

| Home Thoughts | To Work |

| On Broadway | Morning Joy |

| The Barrier | Reminiscences |

| Adolescence | On Broadway |

| Homing Swallows | Love Song |

| The City’s Love | North and South |

| North and South | Rest in Peace |

| Wild May | A Memory of June |

| The Plateau | To Winter |

| After the Winter | Winter in the Country |

| The Wild Goat | After the Winter |

| Harlem Shadows | The Tropics in New York |

| The White City | I Shall Return |

| The Spanish Needle | The Castaways |

| My Mother | December 1919 |

| In Bondage | Flame-Heart |

| December, 1919 | In Bondage |

| Heritage | Harlem Shadows |

| When I Have Passed Away | The Harlem Dancer |

| Enslaved | A Prayer |

| I Shall Return | The Barrier |

| Morning Joy | When Dawn Comes to the City |

| Africa | The Choice |

| On a Primitive Canoe | Sukee River |

| Winter in the Country | Exhortation |

| To Winter | |

| Spring in New Hampshire | |

| On the Road | |

| The Harlem Dancer | |

| Dawn in New York | |

| The Tired Worker | |

| Outcast | |

| I Know My Soul | |

| Birds of Prey | |

| The Castaways | |

| Exhortation: Summer, 1919 | |

| The Lynching | |

| Baptism | |

| If We Must Die | |

| Subway Wind | |

| The Night Fire | |

| Poetry | |

| To a Poet | |

| A Prayer | |

| When Dawn Comes to the City | |

| O Word I Love to Sing | |

| Absence | |

| Summer Morn in New Hampshire | |

| Rest in Peace | |

| A Red Flower | |

| Courage | |

| To O. E. A. | |

| Romance | |

| Flower of Love | |

| The Snow Fairy | |

| La Paloma in London | |

| A Memory of June | |

| Flirtation | |

| Tormented | |

| Polarity | |

| One Year After | |

| French Leave | |

| Jasmines | |

| Commemoration | |

| Memorial | |

| Thirst | |

| Futility | |

| Through Agony |

Works Cited

Gosciak, Josh. The Shadowed Country: Claude Mckay and the Romance of the Victorians. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2006. Print.

McKay, Claude. A Long Way from Home. Ed. Gene Andrew Jarrett. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2007. Print.